Asking the right questions about exploring faith with children

Asking the right questions about exploring faith with children

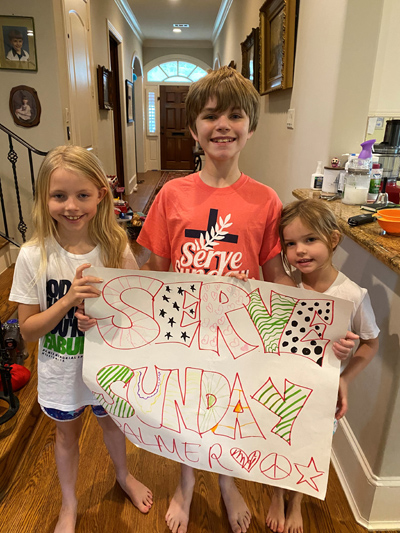

Photo – Community service day went virtual this year at Palmer Memorial Church in Houston | Photo: Palmer Memorial.

Before the coronavirus pandemic, getting ready for church was no easy task for the Larsen family of Wake Forest, North Carolina, writes G. Jeffrey MacDonald in “The Living Church”

It involved cajoling two children, ages six and 10, to be dressed, fed and in the car on time, including days when they’d rather relax at home in pajamas. Mornings didn’t always go as planned, which meant sporadic attendance at Sunday school and gaps in what the kids were learning.

But since Sunday school went online in March, the Larsens have participated in just about every Sunday school session at St. John’s Episcopal Church. For the first time, the kids absorbed all the events of Holy Week, not just the highlights. And now Sunday school includes their mother, Emily, who’s been learning alongside her kids, who are often still in their PJs when the Zoom videoconference begins.

“There’s no excuse anymore not to be there because all we have to do is log on,” Emily Larsen said. “I’ve learned a lot. I never really knew much about Pentecost at all. I had heard the word, but they talked about all the different symbols of Pentecost that I didn’t really know. [Going online] has definitely worked for us.”

Sunday school has been due for a reboot, if not a complete overhaul, educators say. Models forged in the 19th century have struggled to make passionate disciples systematically in the 21st. COVID-19 pandemic conditions have accelerated a process that reformers have longed to see: making Sunday school less academic, more experience-oriented, and more intergenerational.

As programs adapt, they are affirming children’s places in the Church as full-fledged participants who already have a call to ministry. That has been a welcome silver lining to an otherwise disruptive and unsettling pandemic season, said Melissa Rau, the Episcopal Church Foundation’s staff liaison to FORMA, a network for Christian formation.

“Sunday school is absolutely dead,” Rau said. “Not because it’s not worth something, but I think it’s worth more as dessert rather than as meat and potatoes of formation, which really needs to happen at the home.”

She said the Episcopal Church is facing a “discipleship crisis” that can’t be solved by sending kids off to Sunday school lessons twice a month, or however often a family can get there. Sunday school graduates have largely failed to connect the lessons they were taught as children with daily life, she said. What’s needed is more partnering with parents and other caregivers to foster faith-based conversations among family members Monday through Saturday. She sees that happening more during the pandemic because the locus of religious life has shifted from the church building to the home.

“Christian education leaders are becoming more aware and seeing opportunities for re-imagining how they’re pushing into the home now because we’re not gathering on Sundays,” Rau said.

A June 2020 report from the Church of England’s Diocese of Oxford points to how an intergenerational approach to formation has become an urgent need across Western Christianity, according to co-authors Yvonne Morris and Ian Macdonald, both staffers for the diocese. Declining attendance rates in the Oxford diocese since 2015 have been steepest among children under age 17, the report finds. Many feel a “significantly reduced” connection to the church by the time they reach age 15, according to the report.

Parents are primary influencers in laying faith foundations, the report says. But families often don’t live out their faith together. That’s because they aren’t sure what to do. Or they lack confidence to pray together or discuss matters of faith. The report calls for five cultural shifts in Church that would help children to be viewed as pilgrims of equal status with their elders, and as full participants in the intergenerational way of Jesus.

“When a church is asking, ‘How then do we now do Sunday school?’, that might not be the right question,” Macdonald said via Zoom from Oxford. “’How then do we explore faith with our children and young people?’ is a better question because it opens up more possibilities.”

He recommends that families ask this question: How then do we uncover the way of Jesus together?

To help answer that last question, one Oxford diocese parish gave its families a suggested regimen — prayers to say, conversations to have, and activities to do — that provide, in effect, what Rau calls the “meat and potatoes” of formation. In another local church, families in lock down due to the coronavirus have been giving children leadership roles. Kids lead in saying prayers, posing questions about God and giving testimonies of God’s manifestations in their lives.

“There’s been much more equality of leading, guiding and journeying together in families as they shared the joys and difficulties of lockdown and thus being a family of faith together,” Morris said. “It’s been brilliant.”

Pandemic circumstances are now greasing the wheel of change on this side of the Atlantic as well.

Love First at Home engages kids via online Sunday school at Christ Church, Ponte Vedra Beach, Fla. | Photo: Christ Church

Love First at Home engages kids via online Sunday school at Christ Church, Ponte Vedra Beach, Fla. | Photo: Christ Church

At St. John’s Church in Wake Forest, Sarah Bentley Allred is delivering the Godly Play curriculum online via Zoom videoconference. The 30-minute sessions include time for check-in, candle lighting, the Lord’s Prayer, a Bible-based story told with figurines and materials, followed by breakout groups and song before adjourning.

Because Godly Play is story-based, Allred said, it’s conducive to online adaptation. If done alone, the formation impact would be limited, but St. John’s families do it in conjunction with prescribed activities that they weave into their days all week long.

These include prayers for family life in the Book of Common Prayer; reading aloud from a children’s Bible; talking about “what stood out to you” in worship or at Godly Play; sharing highs and lows of the day; leaving a painted rock in memory of a deceased pet in the church garden; and blessing each other, including parents asking children to lay hands on them for a blessing.

“Part of what we’re doing in Godly Play is helping give children some language for talking about their experiences of God, for theologically reflecting on their lives and for using the stories to talk about their lives,” said Allred, who is the director of children’s and family ministries at St. John’s, and also associate for Christian formation and discipleship at Virginia Theological Seminary.

“What’s beautiful that’s happening,” she said, “is that we are now giving that language to their parents as well. I, as the leader of this, am getting to model: how do I discuss scripture with children? Instead of just telling parents, ‘it’s important to ask open-ended questions,’ I’m actually modeling that.”

In some Episcopal settings, the Sunday school shift — away from academic-style instruction and toward intergenerational experiences of Christian living — was underway before the pandemic began. At St. Barnabas Church in Falmouth, Massachusetts, Colette Potts developed a program called Love First. It’s not a curriculum per se as much as a method for practicing in community how to love self, neighbor, and God. Children are recognized for their powers to alleviate suffering, meet needs, and otherwise serve in meaningful ways — not someday in the future, but now.

“A three-year-old can smile, and it can make an old person who’s feeling pain feel joy,” said Potts, who explains the vision in her book, Love First: A Children’s Ministry for the Whole Church. “That’s an amazing superpower that every kid has. So, we are going to point that out to kids, if they don’t already know it, and then we’re going to make them do it all the time because it’s a practice. Caring for others and loving your neighbor take practice. And we’re going to give them opportunities to practice here in our own community so that it comes naturally.”

Love First took off at St. Barnabas in 2016 after the bruising presidential primary season left Cape Cod families craving a kinder, better way of being toward each other, Potts said. Over three years, the Sunday school program swelled from nine kids to 75. She said she knows of 50 to 60 congregations across the country that now use Love First for Sunday school.

One of those congregations, Christ Church in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida, has adapted it for online use in a new, open-source program called Love First at Home. Christ Church’s director of children’s formation and family ministries, Catherine Montgomery, says the intergenerational aspect is so important that she’s thinking about inviting older congregants, who don’t have kids at home, to take part when the younger ones meet on Zoom to do Love First.

“This joy that older people get from being with youngsters — maybe Zoom is a medium for that,” Montgomery said.

Though the academic style might be fading from Sunday school, opportunities for learning biblical content still abound, according to Potts and Montgomery. Looking together at Scripture and noticing such things as how God loves the outcast and the criminal can be a focusing exercise. It challenges Love First participants of all ages to be imaginative and courageous as they aim to go and do likewise.

As experimentation with Sunday school continues, practitioners are grounding it efforts that are at once intergenerational and geared to deliver memorable experiences of the gospel in action.

At Good Shepherd Church in Austin, for instance, parents of elementary-aged children and younger ones have been saying this summer: Enough of the online time. They and their children crave physical interactions if they can take place safely. That’s brought out something new at Good Shepherd: the idea of clustering families this fall by zip code in outdoor settings for small-scale Sunday school activity. Because geography will determine who gets together, further mixing of generations is almost certain.

“We could maybe meet in a park and the children could be able to sit in a circle and experience a story,” said Aimee Bostwick, director of programs at Good Shepherd. “Maybe we can create these opportunities together that everyone shares. Not just the children, but maybe the entire parish.”

USACM2.jpg

USACM1.jpg